1914

One of the NAACP’s missions upon its founding in 1909 was seeking the passage of civil rights legislation in Congress protecting the rights of African Americans. The NAACP launched this struggle in 1914 accordingly:

“Undoubtedly the most important work of the year has been the Association’s vigilance and activity in opposing hostile legislation in Washington. For over a year it has employed a man in each branch of Congress. These men are experts, newspaper men who are trained especially for legislative work. They keep in the closest touch with New York Headquarters and with the District of Columbia Branch, which acts as a Congressional Committee and takes the lead in the local campaign against hostile bills. As soon as word is received of a discriminating measure the Association immediately wires its branches urging them to influence their representatives in Congress to vote against it. Officers, directors and friends of the Association cooperate personally and when necessary representatives are sent to Washington to appear at Committee hearings. No better example of the way the Association is able to work through its branches can be given than the following letter from Judge Brown of the Appellate Court of Illinois, who is President of the Chicago Branch.

Illinois Appelate Court, Chambers of Mr. Justice Brown.

Chicago, January 15, 1915

My Dear Dr. Bentley:

In compliance with your request over the telephone, I take pleasure in sending you a report of the action taken in behalf of our Branch of the National Association in relation to the legislation concerning Negro aliens and also the legislation which passed the House of Representatives concerning intermarriage in the District of Columbia. Immediately upon the passage of the Immigration Act with its prohibition of Negro aliens, I telegraphed for the Branch to the Hon. James Mann, the Hon. Martin Madden, the Hon. Adolph Sabath, in the House of Representatives, protesting against the said amendment and asking them to exert their utmost efforts to defeat it. In these telegrams yourself, Mr. Allinson, Jane Addams, George Packard, Robert McMurdy and Sophonisba Breckenridge personally joined. I also telegraphed for the Branch to the President, requesting him to veto the immigration Bill if it came to him with the prohibition of Negro aliens. The action of the gentlemen named in the House perhaps shows that the telegrams were not needed, but they could have done no harm, and upon the result, from whatever cause, we may congratulate ourselves. The telegram to the President was courteously acknowledged by his Secretary, who said that it would be brought to his attention.

Immediately upon being informed by the press of the passage of the Anti-intermarriage bill, I telegraphed a long night letter to each of our Senators. Senator Lewis was at Hot Aprings, Arkansas, Ill. Senator Sherman was in Washington, and telegrams were addressed to them at these respective points. We referred them to letters written to them in relation to the matter when the bill was before Congress at its last session. We renewed our protest against the legislation, pointing out its injustice, its inexpediency and its futility, and especially indicating both its offensiveness as a studied insult to the Negro race and the great wrong htat it did in taking away from some women the protection which the law afforded to others against men who would take advantage of them. We asked each Senator to exert his influence against the passage of this Act by the Senate. I also addressed a telegram in the name of the Branch by myself as its President, to a dear friend of mine, who is a Democratic member of the House from another State, who has a close acquaintance with many Democratic Senators. I have received from him an acknowledgment of my letter, an expression of sympathy with its object and a promise immediately to use his influence in the line indicated. I am,

Very truly yours,

(Signed) E.O. Brown.

“Following these methods, the Association was able during the year to act upon a flood of discriminating legislation, including anti-intermarriage ills, Jim Crow bills, a bill making Negroes ineligible for service in the army and navy, and residential segregation bills for the District of Columbia. In addition proposed legislation on the subject of rural credits, the University of the United States, vocational education, the extension of the Interstate Commkerce Commission’s jurisdiction to carriers by water, was examined for jokers. Among the bills stifled was the Clark Jim Crow car bill. Such pressure was put on the House to prevent its passage that rather than have it come to a vote it was voted to lay aside District Day, which is the only day on which measures relating to the District of Columbia can be considered. The Clark Bill now goes over until the next Congress where it was probably be defeated most decisively.

“Whenever possible these bills have been stifled in committee. When necessary to fight in the open the Association has done so. When the Aswell-Edwards bill proposing to segregate civil service employees throughout the country came before the Civil Service Reform Committee, Mr. Grimke, President of the District of Columbia B ranch, appeared before the Committee, and as a result of his arguments the bill was never reported. Our fight on the Smith-Lever Bill was not successful. As soon as this was reported to us by our legislative agent it was discovered that though the colored farmers of the South might or might not receive any of the millions which the bill appropriated for agricultural extension work, no specific provision was made for them. To insure colored farmers a fair share of the moneys appropriated the Association persuaded Senator Jones to introduce an amendment providing for this. A scholarly memorandum supporting this Amendment was then prepared by Dr. Du Bois and Mr. Brinsmade and sent to every member of Congress. Both Dr. Du Bois and Mr. Brinsmade went to Washington to attend the hearings on the bill and to interview Congressmen.

“Whenever possible these bills have been stifled in committee. When necessary to fight in the open the Association has done so. When the Aswell-Edwards bill proposing to segregate civil service employees throughout the country came before the Civil Service Reform Committee, Mr. Grimke, President of the District of Columbia B ranch, appeared before the Committee, and as a result of his arguments the bill was never reported. Our fight on the Smith-Lever Bill was not successful. As soon as this was reported to us by our legislative agent it was discovered that though the colored farmers of the South might or might not receive any of the millions which the bill appropriated for agricultural extension work, no specific provision was made for them. To insure colored farmers a fair share of the moneys appropriated the Association persuaded Senator Jones to introduce an amendment providing for this. A scholarly memorandum supporting this Amendment was then prepared by Dr. Du Bois and Mr. Brinsmade and sent to every member of Congress. Both Dr. Du Bois and Mr. Brinsmade went to Washington to attend the hearings on the bill and to interview Congressmen.

“The fight on the amendment lasted for over two days. A substitute, the Shatroth Amendment, was offered, passed by the Senate and then lost. But raising the issue had its effect. Although the allotment of funds is in the hands of the state legislatures, the final disposition really rests with the Secretary of Agriculture, and if he should permit abuse by the states in allotting these funds, the whole matter can be brought up again and thrashed out in Congress. The fight over this bill brought the whole race issue squarely before Congress and before the country, to the surprise and disgust of the more conservative Democrats who were anxious to keep it in the background and little dreamed of its becoming conspicuous as a part of an agricultural extension measure. The debate on this bill was printed in the Congressional Record. A letter of protest from tis Association was read on the floor of the Senate and also appeared in the Record with comments calling attention to the prominent people the Association included in its membership. The name of the Association appeared again and again in the debate and speeches were made by Senators Jones, Clapp, Smith of Michigan, Sherman, Gallinger, Root and others championing our cause. Senator Works of California read a telegram of protest received from our Northern California Branch. Most important of all was the fact that our part in the fight was made clear to the people of the country by the press which gave it the widest publicity.

“We cannot close the account of the Association’s work of the year in Congress without a mention of its activity in securing the reappointment of Judge Terrell who had been nominated by the President. Senator Vardaman had widely announced his intention of defeating Judge Terrell’s confirmation. The Association sent an open letter to Senator Clapp which was published widely in the press to call the attention of the country to the fact that the Southern senators were openly making color a reason for declining to affirm an appointment of the President. Judge Terrell's record on the bench was such that these Senators were unable to find any pretext for this opposition. They were forced to come out in the open. Senator Clapp led the fight to secure favorable action by the Senate on the nomination and was successful.

“In order to bring the race issue before the incoming Congress a questionnaire was sent to all candidates asking them in answer to certain questions to state definitely where they stood. Their answers or their failure to answer were printed and distributed before election by the Association’s branches throughout the country. Particular attention was paid to the pivotal states where the colored vote is of strategic importance. Results were also published in The Crisis, where the Association regularly prints a record of the vote on all legislation discrimination against the Negro. To quote the summary of the results of this questionnaire given in the Crisis: “Perhaps the most striking thing about all these answers is the number of people who frankly say they are not informed on the Negro problem. They simply ‘do not know the facts.’ This is the severest condemnation of the past attitude of the colored people and their friends that culd possibly be made. It is the business of people who want wrongs righted to let the world know just what the wrongs are.” Should the Association have followed the advice of Mr. Peter Ten Eyck, candidate for representative from the Twenty-eight District of New York, one does not like to contemplate what might have been the position of the colored people in the

District of Columbia and ultimately in the whote country. Mr. Ten Eyek in answer to our questionnaire wrote, “It is my advice to you to stop agitating the things which you have outlined in your letter until such time that you ffind that the wild rumors are likable to become a reality.”

“We may congratulate ourselves on the fact that, despite the overwhelming Southern majority I Congress, not a single bill which was directly on its face intended to humiliate or repress colored men and women, was permitted to pass during the year 1914. We do not ask that all the credit for this achievement be given to our Association, but if this Association had never existed it is almost certain that some or all of these bills would have passed. The District of Columbia Branch has been on the firling line in all this work; circumstances have given it the post of labor and of danger and therefore the post of honor; and all men owe it a debt of gratitude for what it has accomplished.”1

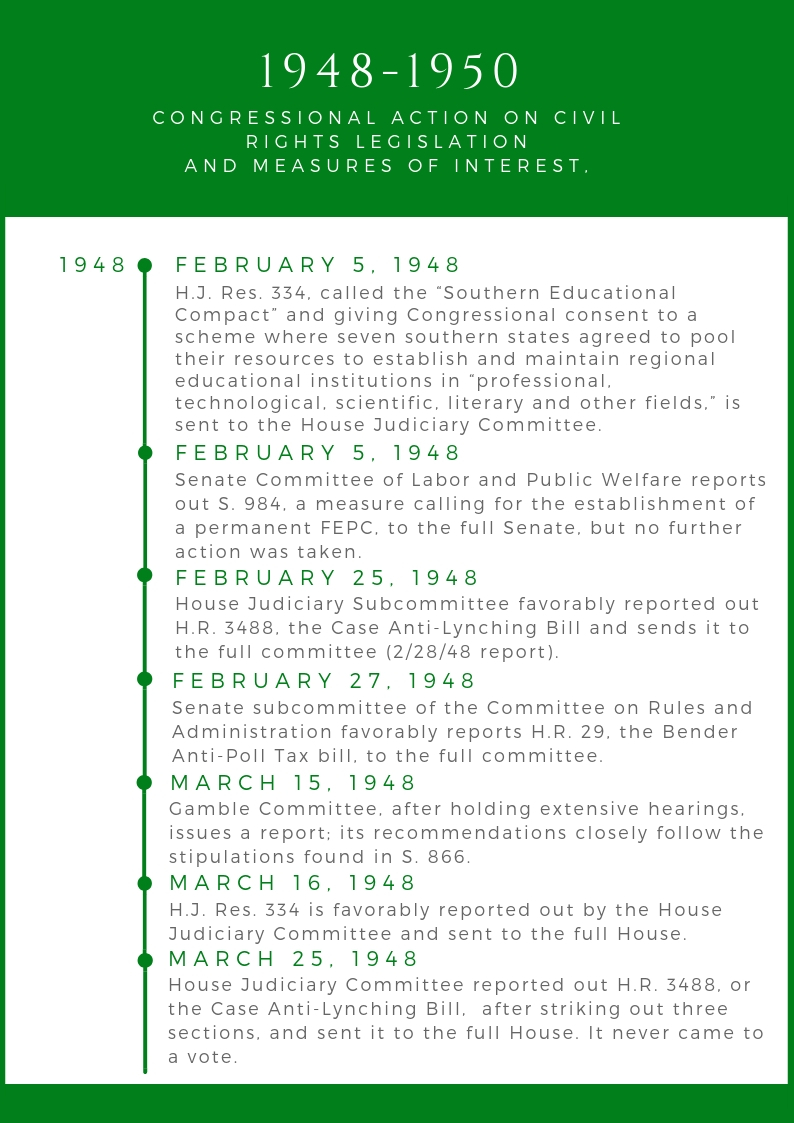

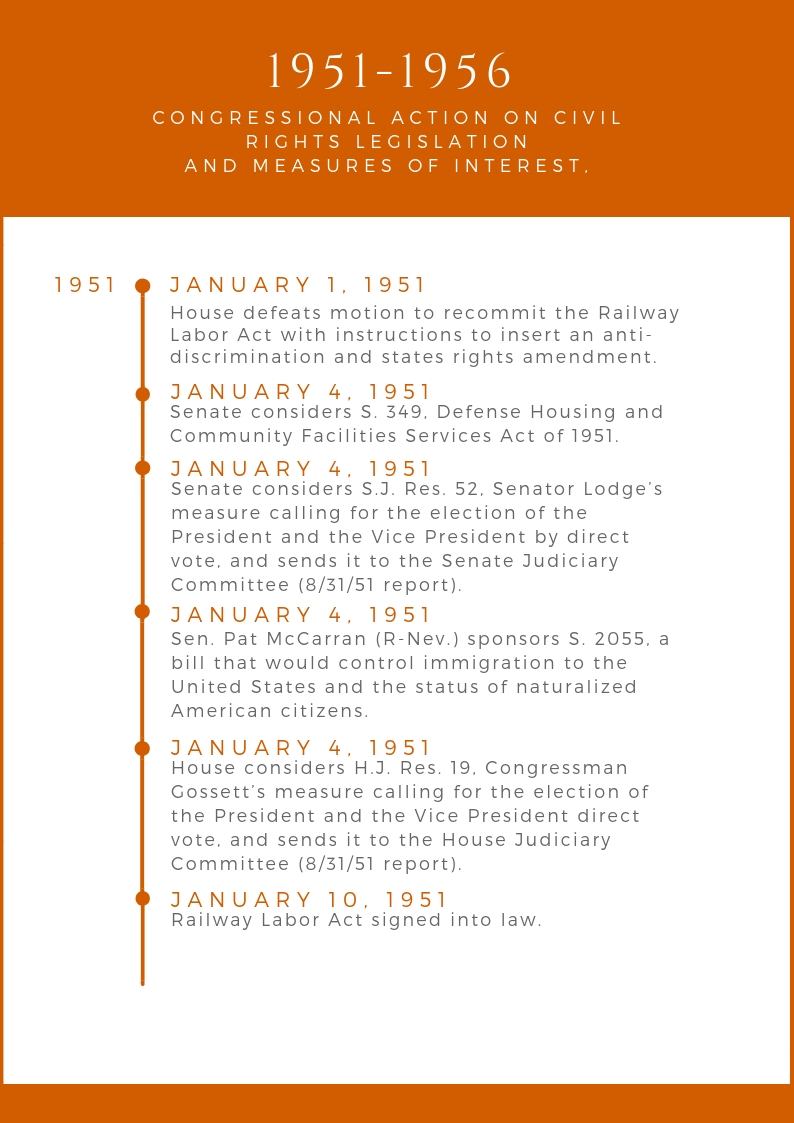

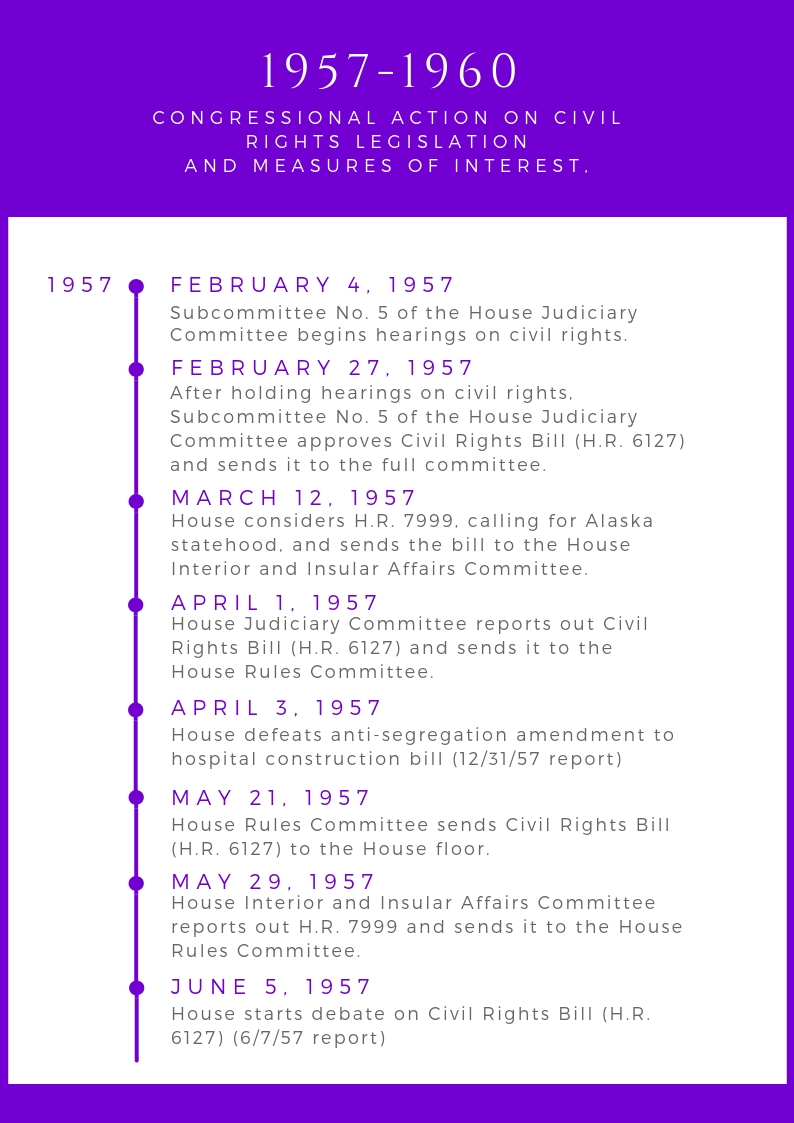

View the timelines to see additional Congressional actions against civil rights legislature spanning the years 1918 - 1960:

For poll tax repeal calendar 1939-1949, see vol. III, pp. ccxlviii-ccli.

For FEPC struggle, see vol. III, pp. ccliv-ccxc

For Jim Crow Travel, see vol. III, pp. ccxcvi-cccxiii.

House Reports

H. Report 1504 on H.R. 7535. See 2/9/56.

1. NAACP, 5th Annual Report, 1915.

Image Credit:

Archibald Grimké (1849-1930)